I wrote recently about data/API services for complex “single page” JavaScript-heavy web applications. Everything there applies to AngularJS as well as other frameworks (Ember, Knockout, React, etc.), but there are some particulars to keep in mind for ease of interaction between an AngularJS web application and a data service. This topic is also asked about in almost every “Angular Boot Camp” class I teach, so by posting this I have an online resource to point at.

Use RESTful URLs and HTTP Methods

By following RESTful patterns rather than inventing ad-hoc patterns for a server API shape, your code will fit in more easily with the rest of the software industry. This reduces the friction in bringing on more developers, in integrating your application with others, and so on. A RESTful server API will operate easily with AngularJS’s built-in mechanisms for working with a server, whether you use plain $http, $resource, or Restangular. For example, all of those already assume that the HTTP status codes indicate success and failure, so do not make up your own way of encoding failure within HTTP “200” success.

Avoid dogma in REST design, though. Most of the time, you can make a server API shape reasonably RESTful with approximately the same implementation effort as something ad hoc. If you have a case where a RESTful design will require substantially more work than something else, consider an “escape hatch”: a portion of your API that isn’t particularly RESTful, hidden behind a generic POSTable endpoint.

Make Data Binding Easy

I assume that by choosing AngularJS, developers aim to leverage its strengths rather than fight it. That means embracing “HTML enhanced”, data binding, and other banner AngularJS features, rather than manually manipulating the DOM (which immediately fails code review here), mostly passing information around using bindings and $watch rather than events, etc.

Therefore, if possible make your data service return data in a shape already suitable for binding in your AngularJS application. Done well, this can reduce the amount of JavaScript code you must write to populate a complex screen to almost nothing. By complex, I mean a screen which contains the modern equivalent of numerous master detail relationships, hundreds of fields, etc.

Of course, JavaScript is a powerful and convenient language for data structure manipulation, so in a sense it does not matter what shape of data is returned from a server; it is always possible to process that data into a shape suitable for data binding. Hence this guideline is oriented toward ease and speed of development when the server code is being written fresh.

(As an aside, I am not 100% sold on data binding; there are other approaches, like that taken by React, which have significant advantages. But if you are using AngularJS, embrace its strengths. Use data binding pervasively.)

Make Commands / Saves Easy Also

Following along from the above, a conveniently and idiomatically crafted AngularJS application will typically yield JavaScript data structures suitable for PUT or POSTing back to a data backend. Make your server accept PUT or POST of updated or new data in the same object “shape” as it returned data. This way, the data can make a round-trip from the server, through data bindings, to be manipulated by a user, then back to the server; all with very little code to write.

This applies to commands (in the CQRS sense) also. If a user is working with the screen via data binding, then that data binding can often yield a data structure ready to send to a server with a couple of lines of code. If you find it necessary to write extensive lines of code to formulate a server interaction, perhaps either your data binding or server should be adjusted stat.

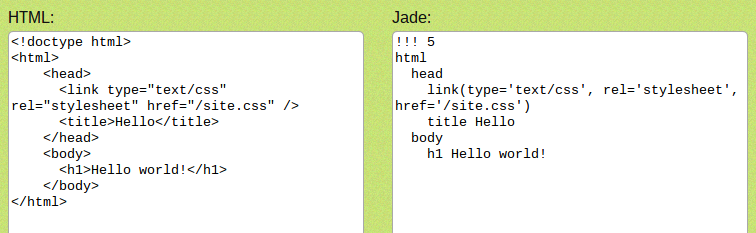

Consider NodeJS on the Server Side, for Code Sharing

Working with complex client-side web development, you will almost certainly use NodeJS in your development toolchain, even if you are not using NodeJS for your data services.

But NodeJS is worthy of consideration for this key reason: it enables code sharing between the front end and back end. With some care in crafting modules, chunks of functionality which must be implemented on both sides of the client/server API (such as validation, but also many kinds of domain logic) can be reused across both, ensuring consistent implementation and eliminating duplication.

There are numerous other platforms worthy of consideration for other reasons. Stay tuned here (and follow me on twitter), I will have more to write about that.

Guard Your Innovation Budget

If your organization is in the process of adopting AngularJS for the first time, consider not simultaneously adopting a new server-side technology. As humans we each have a certain ability to absorb change, and doubly so for organizations comprised of many humans working together. You will probably get better results if you switch to a new client-side development toolkit in a different year then you switch to a new server side development toolkit. I think of this as having an “innovation budget” which can either be concentrated on one layer at a time, or diluted across more than one layer.

Help Wanted

If anyone knows of convenient source code examples already online of doing these things well versus poorly, please contact me – I would love to add links. Given sufficient time I may create the examples, but with the pace of change in our industry these tools could be obsolete before that happens!